ST. JOHN – “You never know what you don’t know,” said St. John the Evangelist parishioner Donna Parker as she listened to historian Dr. Larry McClellan explain the work of the Underground Railroad in Northwest Indiana during a Nov. 19 luncheon hosted by the parish’s Boomers and Beyond senior citizens club.

Parker said she attended “because I have a real interest in history” and learned that thousands of Freedom Seekers journeyed through the Midwest between the 1830s and the Civil War, not up the East Coast, to escape slavery in the southern U.S.

“Thirty years ago I decided to study the Underground Railroad in the Midwest, and it seems more people came through Indiana, Illinois and Ohio than through the East coast of the U.S.,” said McClellan, lead project historian of the Midwest Underground Railroad Network, of his ensuing research.

McClellan explained to the luncheon crowd that there are “two great stories, that of the Freedom Seekers” – a term he prefers over fugitive slaves as respecting their human intention – and that of those who responded and became the Underground Railroad, responding, no initiating. I ask you to re-form your understanding.”

As the Freedom Seekers traveled north, McClellan said, “they came up the Missouri River Valley as a conduit from Missouri and Kentucky and moved up the Illinois River Valley and through Indiana in a separate move from Chicago to Detroit on their way to life as free persons in Canada. Freedom Seekers escaping enslavement from the South … passed through Chicago’s Far South Side at an important point at the Little Calumet River.

There were two west-east routes, McClellan noted, one that hugged the southern shore of Lake Michigan, went through the Dutch settlements of Roseland and South Holland and across the Little Calumet River. This route also passed through the Ton Family farm, established in 1853 and now a National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site.

The other west-east route is Sauk Trail, which used today’s U.S. 12 (Dunes Highway) corridor and the assistance “of a small group (of abolitionists) who were willing to break the law” and face a fine of up to $1,000 for harboring an escaping slave family by allowing them to sleep a night on the family farm.

“Now change it to the brave folks opposing ICE agents,” McClellan compared. “There is a tremendously human dimension to this.”

The Sauk Trail route went from Joliet, Ill. to Detroit, south of the Chicago route, and passed through Michigan City and Westville. As a side note, McClellan pointed out that Charles Osburn, considered “the father of American abolitionism” since he began speaking against slavery as early as 1804, had moved to Westville in 1848 and died there in 1850.

McClellan’s stories about Freedom Seekers like Caroline Qualls, who made her way to Canada as a 16-year-old daughter of a slaveholder and a slave, married and raised six children with her husband, Allen Watkins, another emancipated Freedom Seeker, and helped build a church in their community, were punctuated by the music of Lana Lewis, of Country Club Hills, Ill.

Lewis, a classically trained vocalist and member of the South Holland Master Chorale, opened the program with an a cappella version of “It’s Wonderful World,” which set the tone for later spirituals “Wade in the Water” and “Deep River.”

McClellan also told the story of John and Eliza Little, enslaved on adjoining farms in Tennessee who fell in love, married, and decided in 1841 that “in order to have a life together” they had to run north. Making their way to Illinois, John Little at one point pushed his wife and their meager belongings on a log through a swamp to reach the Ohio River and freedom. When other Freedom Seekers they met up with on their dangerous journey wanted to turn themselves in and beg the mercy of their slaveholders, Eliza said, “I know where I’ve been and I know where I want to go, and I will walk barefoot, if need be, to Chicago!”

“Eliza and John Little ended up walking 370 miles to Chicago” on their way to freedom, McClellan concluded.

The proximity of so many Freedom Seekers to their own community impressed many in the audience. “I didn’t realize that so many slaves came this way to freedom,” said Joanie Ochs. “I had heard of a building in Dyer that was used by the Underground Railroad, but when Mr. McClellan mentioned the Dyer Hotel, I realized it was true.”

Ochs, noting it “would have been very difficult” to risk her own family, said, “I would hope I’d have hidden the Freedom Seekers; I would have been scared, but I hope I would have had the strength.”

Likewise, Jerome and Maryellen Steffe agreed they would have “erred on the side of helping if we had the chance” when the Underground Railroad was operating in Northwest Indiana.

“I thought it was the abolitionists who started it,” Maryellen Steffe said of the Underground Railroad, “so I was surprised to learn that it was the Freedom Seekers who started it, and the abolitionists who responded.”

McClellan urged anyone with an interest in the history of the Underground Railroad in Northwest Indiana to join him and Tom Shepherd, lead project organizer, in continuing to research the Chicago to Detroit Freedom Trail. “We can never forget the brutal reality of slavery and the people who came here as property,” he said.

To learn more about how to get involved in the Midwest Underground Railroad Network, email McClellan at mcclellan.larry@gmail.com or Shepherd at tomshepherd2001@yahoo.com.

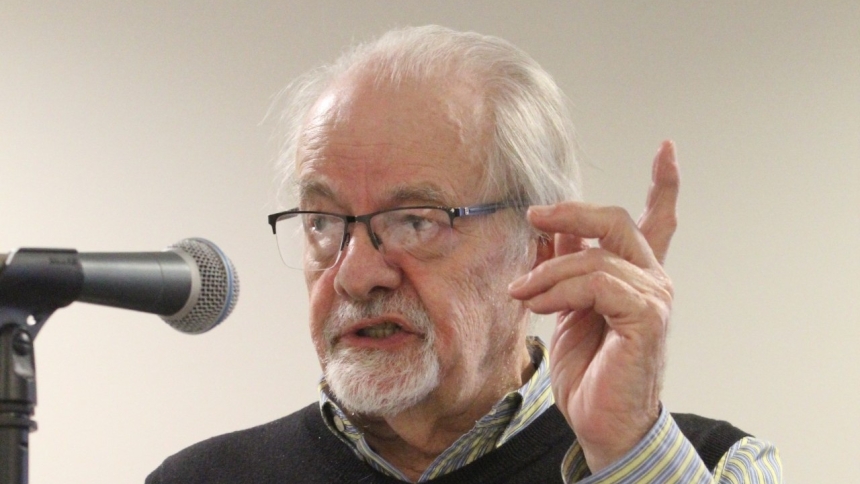

Caption: “People came up the Missouri River Valley as a conduit from Missouri and Kentucky … and through Indiana in a separate move headed to Detroit,” Dr. Larry McClellan, the lead project historian of the Midwest Underground Railroad Network, told Boomers and Beyond members and their guests at St. John the Evangelist in St. John on Nov. 19. He made a plea for local residents interested in history to assist the project research. (Marlene A. Zloza photo)