VALPARAISO – A priest, like any person, needs forgiveness and seeks the mercy of God through prayer and participating in confession as a penitent with a confessor. And like some Catholics, clergymen have unique memories from the sacrament of reconciliation, especially their early experiences.

In this interview feature from a conversation on March 28, Father Douglas Mayer, pastor of St. Paul in Valparaiso, spoke with the Northwest Indiana Catholic. He shared about a first confession queue that gave him something to think about and the ministry that now offers powerful, grace-filled encounters as a confessor.

Asked about “the sides of confession” that he sees, and what his initial impression of availing himself of the sacrament as a child was like, he shared the following:

“Mass was in Latin in my day … until I was ready to start as a freshman in high school,” explained Father Mayer, who grew up in Hobart.

“The funny thing is that I still remember the day of my first reconciliation. It was in the traditional confessionals like you see in the movies – with the priest in the center and two doors, one on either side,” he added.

We also had a brand new young priest, whose name I don’t remember, but I do remember that he played a guitar. Everyone wanted to go to the young priest for confession because he was cool and he wasn’t scary. The (religious) sister did not have us all line up with the young priest, so I was lined up with the pastor.”

Continuing his narrative, Father Mayer said, “So, the first kids go into the confessional, and I’m waiting my turn and waiting my turn … the kids in front of me with the old pastor are coming out of the confessional, but the first kid in the (young priest’s) confessional didn’t come out as the first penitent came out of the old priest’s confessional … and the second, and the third, and the fourth and fifth.”

“So, what was your grade-school mind thinking,” asked the multimedia journalist.

“As little kids, you’re standing there going, wow, what did he do?”

Never fear, a young Doug Mayer’s time was near. “The older priest heard my first confession; he listened to me say my sins and other than it was dark, he had a kind voice,” he said, adding the visit was fast, “without much effort.”

“I thought this is okay, this is not too bad,” he reflected. “I just figure that if the young priest has kept a kid for five kids in a row, how bad is it going to be with the older pastor?”

In that part of the 20th century, psychological counselling, child psychology, and more generally “pop psychology” gained mainstream acceptance. Perhaps the new priest was just detail oriented. Father Mayer can’t say for sure.

“Probably the young priest was trying to use modern methods,” said the Valparaiso pastor.

Growing up and growing in the faith, a teen Doug Mayer continued to seek counsel from his pastors. The church was navigating a sea of change with the interpretation and implementation of the directives of the Second Vatican Council.

“The next memorable moment as a penitent would have been when I was a teenager. It was a different priest and it was after Vatican II, but you still had the chance to use the traditional confessional,” he recalled.

“He recognized my voice and in giving some pastoral advice, he used my name. Then he realized that he really shouldn’t have used my name and kind of was embarrassed. He broke that ‘fourth (wall)’,” explained Father Mayer.

The teenage penitent took some time to ponder the momentary lapse of anonymity.

“I left and did my penance, then thought, this is kind of stupid because when I pick up the phone and say, ‘hello,’ I know who it is on the phone, even though I don’t see them.

“A week or two later, when I didn’t think it was too awkward, I approached (the priest) and said, ‘You know, father, it seems like it doesn’t really make much sense to go into the confessional behind the screen.’”

Certain that the priest had known who he was while confessing, the young man figured he may as well make the sacrament more conversational.

“Hey, can I ask you a favor?” he inquired of his pastor. “And he said, ‘What?’ and I said, ‘Well, the next time I need to go to confession, how about I just call … and we just go for a walk around the block (for the sacrament)?’”

Father Mayer continued his story, “He paused for a moment and said something to the effect of, ‘Well kid, as long as it’s on Saturday and you don’t ask me to do it in the middle of a baseball game, we’ll find a time.’”

Looking back, Father Mayer said that the dedication of the priest to counsel was something, “You can’t ask for more than that.”

After the “interesting” way to approaching reconciliation, the priest and penitent met for a couple more walks, but the clergyman told the young man, “You know, if you don’t mind, unless it’s an emergency, can you use the regular time for confession?”

Father Mayer’s youthful days, when he and his family were parishioners at St. Bridget church, were rich in Catholic practice and culture. His discernment and studies at St. Meinrad Seminary, in St. Meinrad, Ind., at Valparaiso University, and at Sacred Heart School of Theology in Hales Corners, Wisc. led him to ordination to the priesthood in 1986 and pastoral service in a half dozen diocesan parishes.

“As a priest, as a confessor, you have people come in and they’ve already been convicted by the Holy Spirit to turn from some sort of sin, to grow closer to God and ask for His mercy,” he explained. “Sometimes people struggle with just the burden of having a repetitive sin, so you’re able to encourage them to trust in (God’s grace).

“There are sometimes when (you meet) the proverbial lost sheep, or prodigal son, who has been far from the Lord. The privilege of a confessor is when someone comes to see their sins and wants to see and live the way God wants,” said Father Mayer, pointing out that the Gospel reading from March 30 was from Luke 15:1-3, 11-32, The Parable of the Prodigal Son.

“As a confessor you sit there and someone walks through the door in 2025, whether it is face-to-face with someone or behind the screen, hearing about the miraculous movement of the Lord Jesus and the Holy Spirit today – it’s the newest chapter of the Good News!” he exclaimed.

Absolution of sin, by the power Jesus spoke of in Scriptures including John 20:21–23, Matt. 9:8, and 2 Cor. 5:18, is a gift the fruits of which lead the penitent to peacefully and productively continue their work in the vineyard.

Father Mayer concluded, “Whether we’re struggling with the repetition of a sin that is a thorn in our side like the mysterious thorn that St. Paul begged the Lord to take away, or whether we’ve fallen into grave sin, and by His mercy have begun to trust that He can forgive us… In all our situations, to be able to reassure someone with the words and teachings of Jesus, can be very powerful for them.

“We need to rejoice in that moment of reconciliation and what’s so beautiful, of course, for the priest, is that you see the power of the Holy Spirit and the Risen Lord working in their lives!”

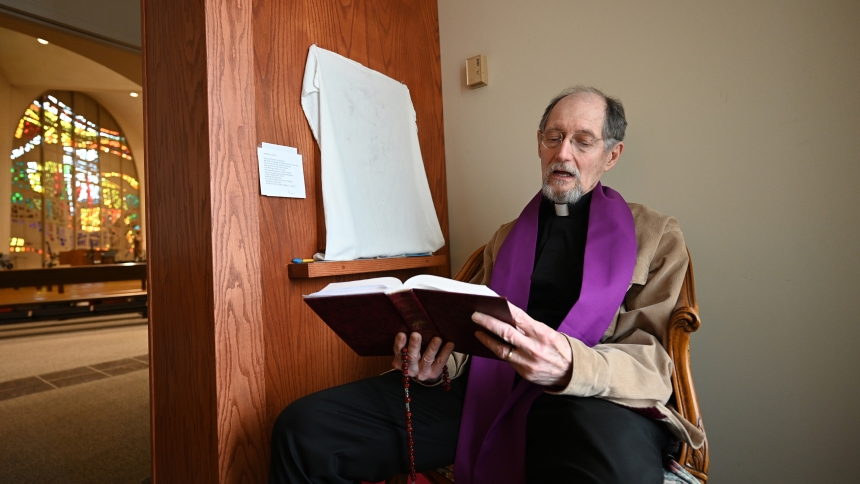

Caption: Father Douglas Mayer, pastor of St. Paul, prays in the confessional at the Valparaiso church on April 9. A penitent experiences the "power of the Risen Lord" in the sacrament of reconciliation, according to Father Mayer, who recalled his own journey of sacramental forgiveness. (Anthony D. Alonzo photo)